Decades of Research Find No Support for Learning Styles

Preamble: I’m sorry, this post is a bit long. Future posts will be shorter, I promise!

I’m confident you’ve probably heard of learning styles and the assumption that there is one best way for each person to learn. You might have heard people say “I’m a visual learner,” or “I learn best by doing,” or “I learn best by listening.” Learning styles theory proposes that everyone has a unique way in which they learn. Within learning styles theory, it’s the meshing hypothesis that suggests that if we match the instructional design of a lesson to a student’s learning style, then the learner will retain the material better.

So for example, if a learner identifies as a visual learner, and we design a lesson filled with images and diagrams, the meshing hypothesis predicts this learner will understand and retain the material better than if they were given a lesson that does not align with their preference, such as one based mainly on audio.

Would you believe it if I told you there have been more than 70 models of learning styles conceived over the last 120 years? It’s true! Here’s just a few of the more popular ones (Coffield et al., 2004; Mayer & Fiorella, 2021):

- Visual, auditory, kinesthetic or tactile learners (VAK/VARK model, by Burke Barbe and later iterated on by Neil Fleming)

- Convergent, divergent, assimilating, or accommodating learners (David Kolb’s model)

- Field dependent or field independent learners (Herman A. Witkin’s model)

Now, you might reasonably assume that because learning styles have been around for a long time, and because so many different models exist, the core idea—that people have distinct learning styles—must be supported by strong empirical evidence. You may also assume that our confidence in learning styles theory should be similar to our confidence in other well-established educational principles, like cognitive load theory. However, as we’ll see, this is not the case! When we’ve run well-designed experimental tests on learning styles theory and the meshing hypothesis, the results keep coming back showing that there are no significant differences between lessons that cater to different learning styles and those that don’t.

Pashler et al.

Pashler et al. (2008) is one of the most frequently cited papers that explores the research around learning styles. The authors found that while learning styles and the meshing hypothesis have gained significant popularity, very few studies have sufficiently robust study designs that would allow them to reliably determine if the meshing hypothesis is supported or unsupported by empirical evidence.

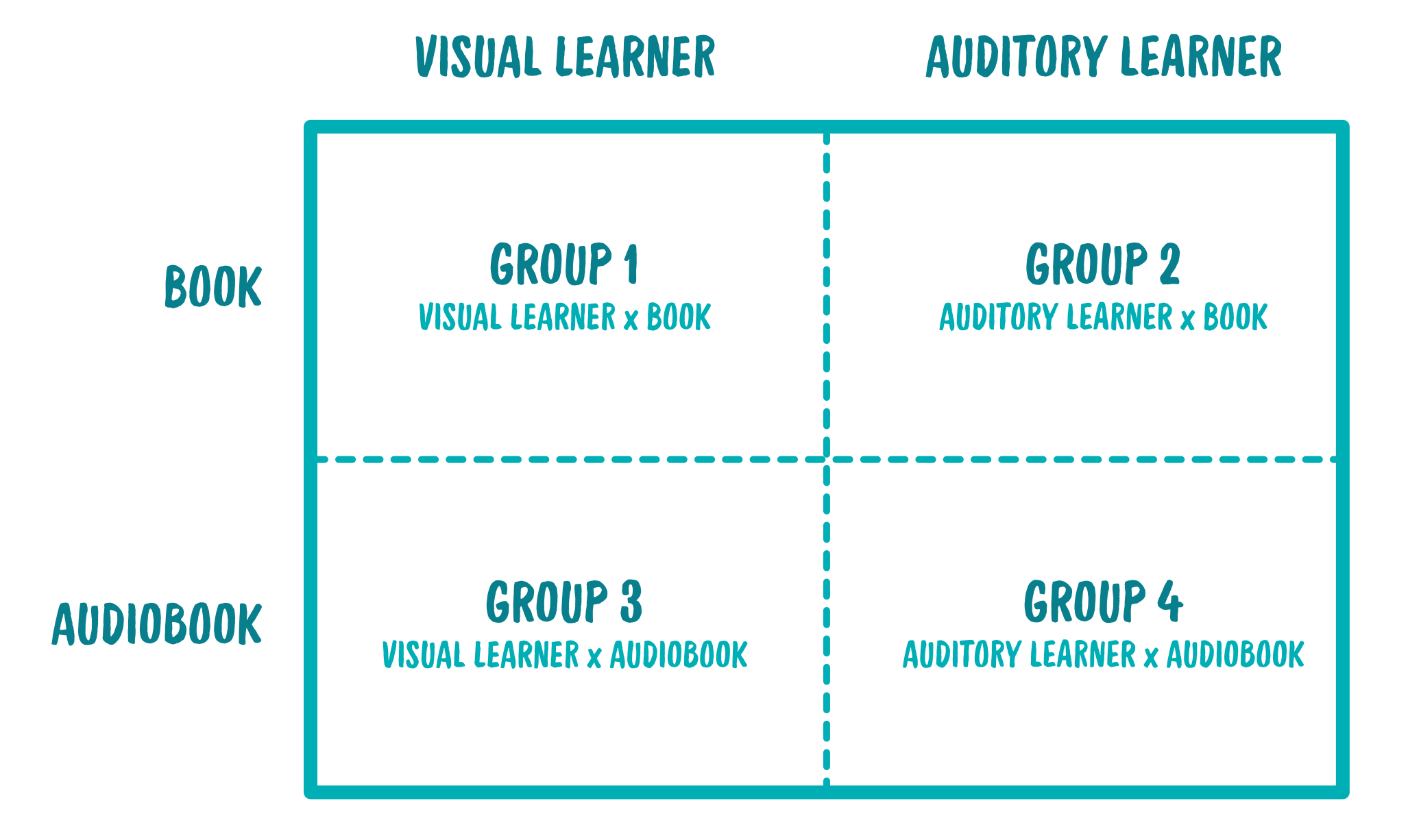

So to address this, Pashler et al. proposed their own study design. They suggested a factorial randomized design would be the most effective way to confirm or reject the meshing hypothesis. In short, a factorial randomized experiment is a study where participants are randomly assigned to different combinations of two or more variables (e.g., learning style × type of instruction) so researchers can test not only the separate effects of each variable but also whether the variables interact with each other to influence outcomes.

In the context of learning styles research, the study must demonstrate a clear crossover interaction, meaning one instructional method should produce the best outcomes for one learning style group, while a different method should produce the best outcomes for a second learning style group. For example, visual learners should perform better with books than audiobooks, while auditory learners should perform better with audiobooks than books. Without this pattern, the meshing hypothesis is not supported.

After describing their proposed study design, the authors then reviewed the body of existing learning styles literature to see which ones used a factorial randomized design. Almost none of them did, and of the few that did use the design, their results did not support the meshing hypothesis, leaving us no reason to support its ongoing legitimacy.

Rogowsky, Calhoun, and Tallal

A few years later, Rogowsky, Calhoun, and Tallal (2015) conducted an empirical study designed to meet the methodological standards outlined by Pashler et al. (2008). The authors focused on auditory and visual word-learning preferences in 121 college-educated adults. (Yes, admittedly this is quite a small sample size.)

First, the researchers determined each participant’s preferred learning style. All participants completed a standardized online learning-style questionnaire that classified them as either preferring to learn new information by listening to it or reading it.

Second, the researchers measured each participant’s actual listening and reading comprehension abilities. Every participant completed two ability tests: one where they listened to short recorded passages and answered comprehension questions, and another where they silently read similar passages and answered comprehension questions. These tests allowed the researchers to compare what participants preferred with how they actually performed in each modality.

Third, the participants were randomly assigned to one of two instructional conditions. Half of the group listened to a digital audiobook version of a nonfiction text, while the other half read the exact same material. To be clear, all participants received the exact same content, presented in just one of the two formats.

Finally, the researchers assessed how well participants learned and retained the material. First, immediately after completing the study session, the participants answered a written comprehension test covering the passage. Then, two weeks later, they completed the same test again online without reviewing the material. This allowed the researchers to compare immediate learning and longer-term memory across both learning-style groups and instructional formats.

This study set out to answer two central questions:

- Whether learning-style preference was related to verbal comprehension aptitude in listening or reading. The results showed no statistically significant relationship. Instead, participants who preferred learning through reading outperformed people who preferred listening, on both listening and reading comprehension aptitude tests.

- Whether matching instructional format to learning-style preference improved learning. The results showed learning outcomes didn’t improve when instructional format aligned with a learner’s stated preference.

In summary, the study found no evidence supporting the meshing hypothesis for verbal comprehension. The authors concluded that aptitude—not preference—is the stronger predictor of performance, and that routinely accommodating auditory preferences may be counterproductive if it limits the development of visual word skills.

A quick tangent: There are some similarities here with findings in medicine, where a clinician’s age and years of experience are poor predictors of patient outcomes, while performance on aptitude measures is a stronger predictor (Ericsson et al., 2018, pp. 928–932). Hrm!

A small selection of other research on learning styles

While I’ve introduced you to two papers here, there has been much moremresearch done on learning styles. I want to emphasize how long we’ve been studying learning styles with shaky results (at best) and therefore have very strong grounds to be highly skeptical of learning styles. These studies highlight how confident we should be that the results of the two studies I described earlier are not unique.

- Kampwirith, T., & Bates, M. (1980) - This review found that matching teaching methods to children’s preferred auditory or visual modalities is largely unsupported by research, with most studies showing no benefit—or even better outcomes when teaching non-preferred modalities—despite widespread belief among educators.

- Doyle, W., & Rutherford, B. (1984) - This article reviews research on learning-style matching and concludes that no single learner preference dictates instruction. Rather, most students adapt to various teaching modes, and uniform instructional methods are often more practical and effective than differentiated approaches.

- Curry (1990) - This article argues that despite claims that learning styles can improve curriculum, instruction, assessment, and student guidance, their application is undermined by unclear definitions, unreliable measurement, and difficulty identifying relevant learner characteristics.

- Constantinidou, F., & Baker, S. (2002) - This study found that while older adults (when compared with younger adults) recalled fewer words overall, both age groups learned at similar rates, and visual or combined visual-auditory presentations led to better memory performance than auditory presentation alone.

- Massa, L. J., & Mayer, R. E. (2006) - This study found no meaningful evidence that verbal or visual learners benefit more from matched multimedia instruction, suggesting that tailoring help-screens to individual learning styles does not improve learning outcomes.

- Husmann, P. R., & O’Loughlin, V. D. (2018) - This study found no relationship between students’ VARK learning styles, their chosen study strategies, and anatomy course performance, showing instead that specific study methods—not learning-style alignment—predicted better outcomes.

- Seddik, M., Attou, Y., & Benaissa, M. (2025) - This study found that tailoring English instruction to students’ preferred learning styles did not improve performance in listening, speaking, or writing.

The list goes on. I think you get the picture.

Why are learning styles still so popular?

So why does the idea of learning styles persist after all this time and all this evidence? Pashler et al. have some ideas:

- People like being categorized into “types”, and type-based models, such as horoscopes and the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator test. These type-based models have strong intuitive appeal, but are not supported by empirical evidence.

- It offers a simple solution -namely, that everyone can succeed if the instruction is matched to their learning style, offering an optimistic message about learning potential, and an easy framework to follow to achieve that.

- It shifts responsibility away from the learner, making it easier to attribute poor performance to inadequate teaching rather than an individual’s intrinsic ability or the amount of effort the learner applies when learning.

- There is industry with financial stakes in learning styles. Companies publish learning style assessments, guidebooks, and professional development workshops based on the idea that learning styles do exist, and make revenue from them.

I would like to add one more reason to the list above. Learning styles just feel intuitively true. This is because we hear about learning styles throughout our education systems—from institutions we trust, professional development workshops, and training programs—so when everyone is talking about it, it feels right. The same thing happens with the belief that sugar makes children hyperactive; it doesn’t, but it feels like it does. Textbooks and teacher education continue to repeat the learning styles myth, and outdated materials pass it to each new generation of educators. I can attest that I was taught about learning styles during my Master of Education degree, and it was framed as an evidence-based theory.

If you’re like me, you might feel like the persistence of this myth (and others like it) is really quite frustrating. I feel like Mayer and Fiorella (2021) really capture my feelings about this whole situation:

“Indeed, it might be suggested that the continuing belief in the utility of learning styles by educators, despite decades of contrary evidence, is a distressing indicator of the lack of evidence-based practice in education and in university-based teacher education programs.”

And this is partly why I decided to start a newsletter.

Learners are still unique individuals

While learning styles theory has no ground to stand on, I want to be clear that every learner is unique. They have different backgrounds, experiences, and working memory capacities. Some learners may also require accommodations for sensory disabilities or neurodivergence. But despite these differences, the underlying cognitive mechanisms involved in learning are largely the same across humans. There is no good reason to believe that adhering to someone’s learning preferences will not improve learning outcomes.

Learners can’t reliably pick the best instructional experiences for themselves

In fact, Clark (1982) shows that when learners are given the opportunity to pick from a variety of instructional experiences, they often pick the experience that is least beneficial to them. He found students with high academic ability tended to learn more from less structured, open-ended instruction that required them to plan, organize, and use their own learning strategies. But these high achieving students tended to prefer very structured lessons with lots of hand-holding by the instructor, perhaps because they were more familiar with these types of lessons and felt familiar instruction would require less effort on their part. Conversely, low achieving students were the opposite. They learned more from the more structured lessons, but preferred the less structured lessons, possibly because they felt they drew less attention to themselves and their academic performance in less structured environments.

In summary, Clark’s findings suggest students want the best results for the least effort and they routinely misjudge the effort involved in the lessons they gravitate toward. And one of the golden rules of learning is that you need to put in cognitive effort to learning something. The more effort you put in, the better your learning outcomes.

Applications for healthcare instructors

To tie this all together, here’s some actionable takeaways I suggest:

- Be vigilant when you hear people discuss learning styles or a learner’s preferences, especially when they propose aligning instruction to match a learner’s preferences.

- Don’t let learners pick their own educational material. This includes telling them to search YouTube or another search engine for a lesson. Students will gravitate towards content they perceive will require less cognitive effort. As the instructor, you must decide what learning resources suitable for your students.

Coming up next...

Now, after all this you might be thinking, does any of this matter? What harm is there in letting people believe learning styles exist? I’ve had a few of my friends and colleagues ask me this recently. I’ll dig into this more next time!

References

- Mayer, R. E., & Fiorella, L. (Eds.). (2021). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108894333

- Clark, R. E. (1982). Antagonism Between Achievement and Enjoyment in ATI Studies. Educational Psychologist, 17(2), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461528209529247

- Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 9(3), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x

- Rogowsky, B. A., Calhoun, B. M., & Tallal, P. (2015). Matching learning style to instructional method: Effects on comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037478

- Kampwirth, T. J., & Bates, M. (1980). Modality Preference and Teaching Method: A Review of the Research. Academic Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1177/105345128001500509

- Doyle, W., & Rutherford, B. (1984). Classroom research on matching learning and teaching styles. Theory Into Practice, 23(1), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405848409543085

- Curry, L. (1990). A Critique of the Research on Learning Styles. Educational Leadership, 48(2).

- Constantinidou, F., & Baker, S. (2002). Stimulus modality and verbal learning performance in normal aging. Brain and Language, 82(3), 296–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0093-934X(02)00018-4

- Massa, L. J., & Mayer, R. E. (2006). Testing the ATI hypothesis: Should multimedia instruction accommodate verbalizer-visualizer cognitive style? Learning and Individual Differences, 16(4), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2006.10.001

- Husmann, P. R., & O’Loughlin, V. D. (2019). Another Nail in the Coffin for Learning Styles? Disparities among Undergraduate Anatomy Students’ Study Strategies, Class Performance, and Reported VARK Learning Styles. Anatomical Sciences Education, 12(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1777

- Seddik, M., Attou, Y., & Benaissa, M. (n.d.). The meshing hypothesis revisited: A quasi-experimental study of the impact of tailoring English instruction to learning styles on academic performance. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 0(0), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2025.2564357

- Ericsson, K. A., Hoffman, R. R., Kozbelt, A., & Williams, A. M. (Eds.). (2018). The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316480748