The Scientific Method

How a learning theory is born.

For my first real post, I want to briefly review the scientific method. I’m confident most of you are already familiar with it, so I won’t go into too much detail. The reason I’m bringing this up is because we’ll be referring back to this process quite often in future posts. So please stick with me — this is important!

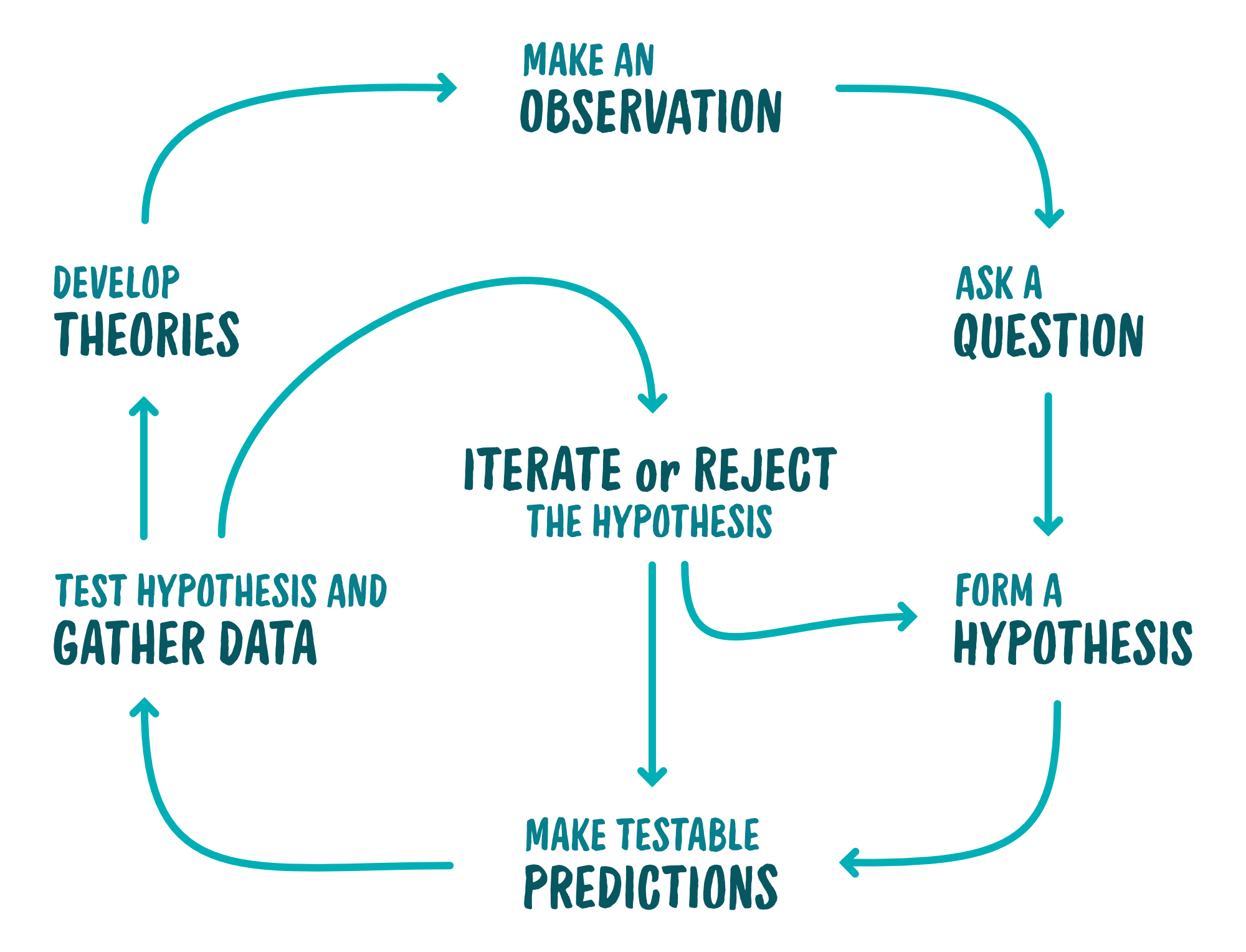

Here’s a diagram summarizing the process:

Make an Observation

All research begins from observation. At some point, we take note of something that perplexes us and that we want to investigate further. For example, you might observe learners completing their workplace orientation don’t seem to be retaining much the information that’s taught to them. Instead, their preceptors (i.e., more senior professionals who show them the ropes) are having to re-explain many concepts that were covered in orientation.

Ask a Question

Based on this observation, we next ask a question. In our example above, it could be a simple as “Why aren’t learners retaining information presented in orientation?”

Form a Hypothesis

Although there are many possible causes that might explain the observation we made and the question we asked, it’s impossible to test them all. (And even more impossible to test them all at once!) Instead, we narrow in on a very limited number of potential explanations for the observation - deductions. If we can test these deductions using the scientific method, that’s when our explanation becomes a hypothesis.

Using the example above, maybe learners aren’t retaining information because the orientation environment is filled with distractions. Maybe the orientation room is beside a high-traffic hallway, and the sound of foot traffic and passing conversation leaks into the room. Maybe the room is physically too small to house all the learners comfortably. Or maybe someone from IT is roaming the room to assist learners with computer login issues, which is distracting to learners. The overall hypothesis here is that the learning environment is affecting the learners’ retention of information delivered in their workplace orientation.

Make Testable Predictions

With this hypothesis in mind, the next step is to design a way to test our predictions. The design of our test is important, because the better we design our test, the more confidence we can have in the accuracy and meaningfulness of our results. That said, it’s often not possible to have a perfect study design, especially if we’re hoping to conduct experiments. Often there are tons of constraints we have to account for, such as time, financial, or geographical constraints, to name only a few. So we often have to make the most of the available resources.

Here’s a simplified list of things we should consider when setting up a test of our prediction(s):

Selecting a Sample: Ideally, we want a group of participants (a sample) that’s big and diverse enough to generalize our results to a broader population. The goal isn’t necessarily to generalize to the entire world, but at least to a culturally similar population beyond our own institution — like an industry, province, country, or continent.

Choosing a Research Approach: Next, we must decide on whether to conduct quantitative or qualitative research.

- Qualitative research helps us understand the meaning behind human behaviour, it excels at exploring motivation, perception, or experience.

- Quantitative research, allows us to measure what changes and by how much. It’s particularly useful for evaluating instructional strategies and assessing improvements in learning outcomes.

While both approaches are valuable, I’ll focus primarily on experiments and quasi-experimental studies that use quantitative inquiry to examine data-driven educational strategies and their impact on learner performance.

Controlling for Confounding Variables: If we decide to go the quantitative research route, we need to control for confounding variables — factors that could influence the results in unintended ways. By doing so, we ensure our findings reflect what we’re actually trying to test, rather than something else entirely.

A common mistake I often see in educational psychology research is failing to control for time spent learning. For example, researchers may have a control group and an experimental group. The experimental group receives the same instruction as the control group, plus the additional experimental instruction being tested. Meanwhile, the control group receives no extra instruction. It’s not surprising, then, that the experimental group tends to perform better. It turns out the more time you spend learning something, the better you remember it! As a result, these kinds of studies contribute little to advancing the field, since the improvement can be attributed to increased learning time (that is, the confound) rather than the intervention itself.

Reliable measurement: Finally, we need to figure out a reliable way to measure whatever outcome we’re investigating. If we’re trying to measure knowledge retention, we might want a test at the end of the lesson so we can objectively assess what learners remember. And then maybe we could administer another test a few weeks later (or a series of tests staggered over the next few months) to see how retention changes over time.

Sometimes researchers will administer questionnaires asking learners to reflect on their performance. While these can be valuable for understanding individual beliefs or opinions, they are not ideal for measuring learning outcomes. Learners often don’t have the introspective skills required to accurately assess their own knowledge or the quality of their learning experience. Even those who do possess these skills typically can’t evaluate their knowledge at a detailed level.

Test Hypothesis and Gather Data

After all the preparation, we can finally move on to testing our hypothesis and collecting data. Sticking with our earlier example, we might measure knowledge retention and application among a group of learners in a distracting environment, then test a new group of learners in a distraction-free environment. By comparing the post-orientation test scores of both groups using robust statistical methods (a t-test in this case!), we can determine which cohort performed better and whether this difference is statistically significant. We might also consider whether this result is practically meaningful.

Iterate or Reject the Hypothesis

Once we have gathered and analyzed the data, we should have enough information to determine whether our hypothesis has merit. If the evidence doesn’t support our proposed explanation, that’s okay. We can either form a new hypothesis and test that, or we can refine our experiment to see if a different approach will give us new insights.

What we shouldn’t do — and this is important — is to reformulate our hypothesis based on the data of our original experiment, and present it as though it was our original hypothesis all along. Unfortunately, this practice is very common — so common, that it has its own term “HARKing”, or hypothesizing after the results are known. Researchers, eager to publish positive results, may reframe their hypotheses post hoc in order to report a “significant” finding. This practice introduces methodological flaws and clutters the field with misleading studies, making it harder to identify truly impactful research.

Develop Theories

If our results support our hypothesis, then we can continue to test the same hypothesis under different conditions (e.g., with different groups of learners, in different settings), until we feel confident enough to have a working theory that explains what might be happening in our original observation.

Theories are overarching frameworks that propose why our explanations (or hypotheses) might be true and why we’re observing what we are in our experiments. Theories are what pull together the findings of various research studies to make sense of them on a broader scale.

Returning to our example, let’s say learners in the distraction-free room scored, on average, 10% better than learners in the distraction-filled room — a finding that is potentially both statistically significant and meaningful. From this, we might reasonably conclude that learners learn best in a distraction-free environment! This evidence supports our hypothesis, and it’s a good start, but it isn’t a theory. Our theory, in this case, could be that being in a distraction-free environment lowers the cognitive load that learners are facing and improves memory encoding and storage, which would explain the improved test results. This theory then allows us to connect our research finding — that learners perform best after learning in a distraction-free environment — to a whole literature on cognitive load and memory. Theories provide us with a stronger anchor for our research findings because they give us reasons why our hypotheses and observations came to be.

And at this point, the cycle should begin all over again. Once we’ve have a working theory, testable hypotheses, and robust observations, it might be tempting to say, “Case closed! We’ve solved it!” However, this is risky and premature because there is a very real possibility that our results don’t always hold true. This realization is an important one because it can lead us to hypothesize boundary conditions—the specific situations or contexts in which our theory applies, and those in which it doesn’t. We need to test edge cases to see when and when our explanations might not apply. In terms of our example, maybe learners who have had previous exposure to the material they’re learning might not be as bothered by distractions — this would be an important edge case (i.e., boundary condition) to discover.

Why is this important?

I’ve made a point of reviewing this because, as we’ll explore in later posts, there is a lot of misinformation swirling about within the education field. This is partly because learning theories founded on evidence that doesn’t adhere to the scientific method are given equal—or even greater—credibility than those that have been rigorously developed and tested through scientific research.

This causes problems when we design our educational experiences based on theories that we believe hold true, but which in reality may:

- Have never been tested at all.

- Have been tested and have no reliable data to support them.

- Have been tested but show only negligible impact on learning outcomes.

To give a concrete example, as I was writing this post, a new report from the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel landed in my inbox. The panel noted that nearly 70% of children aged 10 in the Global South cannot read and understand simple text—largely due to a failure to use teaching methods proven effective by research (1).

In my next post, we’ll look into one of the most persistent and widely believed myths in educational psychology: learning styles.

References: